|

(Color photos courtesy of Michael Padwee unless otherwise noted.)

|

There are many buildings throughout the United Kingdom that have artistically benefitted from the ceramics industry, which was a major part of the industrial revolution in 19th century England. This is the story of one of those buildings. I had heard of the Michelin Tyre Company building in the Kensington/Chelsea section of London and decided to photograph it one morning. Recognizing that England had the highest density of vehicles in Europe, in 1907 Michelin decided to build a new head office in London for it’s English branch. “With Michelin House in London, Michelin innovated and used giant decoration as a communication tool.” (http://bibendum-in-museums.michelin.com/indexen.htm) This building, now an office building and department store at 81 Fulham Road (at Sloane Road), is covered with ceramics and has thirty-four tile panels, mostly of early automobile races, on two sides of the building facade and in the interior. According to Lynn Pearson in her Tile Gazetteer, the Michelin Building was commissioned in 1909 and opened in 1911 as the British headquarters of the Michelin Tyre Company; the facade, which hides a reinforced concrete frame, “is mostly white Burmantofts Marmo* cladding with blue, yellow and green highlights, and a series of high relief faience blocks with assorted tyre-related imagery from rubber plants to interlocking wheels." (Lynn Pearson, Tile Gazetteer, Richard Dennis, Somerset, UK, 2005, p.227)

|

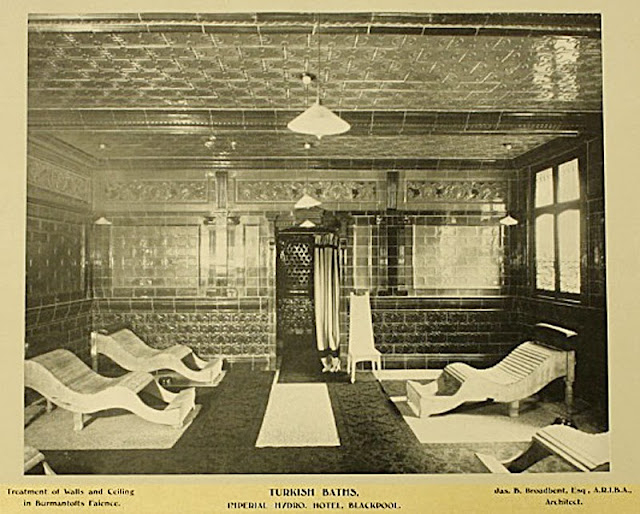

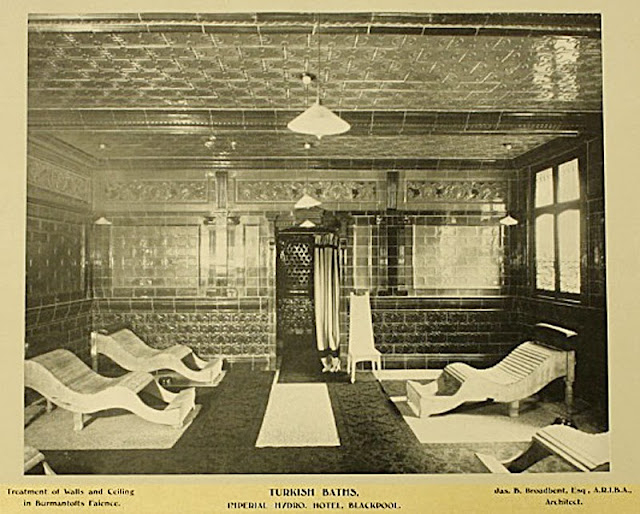

| Ceiling and Wall treatment with Burmantofts Faience in a Turkish Bath, Blackpool. (Burmantofts 1902, Catalog published by the Burmantofts Works, Leeds, unpaginated) |

|

| Part of the booking hall wall of bottle-green glazed faience blocks, most probably Burmantofts, in the Nottingham Midland Railway Station, built in 1904. |

*[Burmantofts Marmo was a type of faience produced by the Leeds Fireclay Co., Ltd. from about 1908 on after brightly colored tile and faience exteriors went out of fashion in England in the early 1900s. Leeds Fireclay Co. was an amalgam of five companies in 1889, including Burmantofts Co., Ltd. Burmantofts Marmo was produced in direct competition with Doulton’s Carreraware. Marmo faience “was covered with a matt egg-shell glaze and made to withstand the ravages of frost, rain and soot-laden air; it was used for many buildings throughout Britain between 1910 and 1940....,” (Lynn Pearson, p. 463) such as the Thornton Building in Leeds below.

|

| Another building clad with Burmantoft's Marmo faience is the Thornton & Co. Building (1918) in Leeds. (Photo courtesy of Paul Thompson of West Yorkshire Images) |

Although the main ceramicized facade of Michelin House takes up a small frontage on three sides of the block, the entire Michelin building takes up one full block. “The building, at Fulham Road in the Chelsea section of London, was designed by Françoise Espinasse (1880–1925), who was employed as an engineer in the construction department at Michelin’s headquarters in Clermont-Ferrand, France. While the building was designed and built at the end of the art nouveau era, it is difficult to define a specific architectural style for the building. It is an eclectic mix of art nouveau and art deco styles and graphic motifs evident in several prominent elements on its facade, as well as in its interior." (Lynn Pearson, p. 227)

The building is architecturally described as follows by “British Listed Buildings”: “Two storeys, concrete and brick construction faced with glazed terra-cotta. Three bay front, the ground floor divided by ornamental piers, with ornamental ironwork below lintels. Ornamental cornice over. Large round arched central window with shaped gable over with tyre models as kneelers. Windows to right and left with rectangular heads beneath ornamental panels decorated with wheels and foliage. Small octagonal corner turrets to full height but with some red brick.

"Left hand return of 9 bays, right hand of 5, with further, simpler windows behind. Return sides continued in similar style. Segmental and square headed windows on ground floor. First floor windows flat headed with words 'Michelin Tyre Company Limited Bibendum' over. Ends with windows between piers; ornamental frieze between storeys. Open segmental pediments at intervals with inset faience tyres. The material is Burmantofts Marmo facing. Series of pictorial tile panels on the side elevations (ground floor) and inside the drive-in by Gilardoni Fils of Paris. The panels represent the racing successes of cars with Michelin tyres between 1900 and 1908, and in the fitting bay Edward VII and Prince George in their Michelin type fitted car.” (http://www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/en-203794-michelin-house-the-main-part-facing-the- )

“The building’s exterior tiled facade is a colorful, three-dimensional advertisement for the company with a composite of promotional images containing hand-painted pictorial panels manufactured by famed Parisian tile maker Gilardoni Fils et Cie (est. 1880) and depicting scenes of early-twentieth-century motoring. Typographic and numeric panels identify Michelin and related advertising slogans in letterform styles of the time period. Etched glass street maps of Paris appear in a number of windows along the first floor, and decorative metalwork carries stylized typographic monograms of the company. Two glass cupolas, which appear as if they are a pile of tires, frame either side of the building’s entrance.

|

| The back--Lucan Place--side of the building with Michelin “M”s in the brickwork. |

“Three large stained glass windows grace the interior, all featuring the Michelin Man or “Bibendum,” and are based on Michelin advertisements of the time period. Bibendum, designed by the French artist and cartoonist Marius Roussillon (1867–1966) and commonly referred to as the Michelin Man, is one of the world’s oldest trademarks… .” (R. Poulin, “ Graphic Design + Architecture: A 20th-Century History"; http://www.newyorkspacesmag.com/New-York-Spaces/January-2013/Graphic-Design-Architecture-A-20th-Century-History-by-Richard-Poulin/)

Michelin left the building in 1985, and, following restoration which was completed in 1987, the building reopened as an office, shopping and restaurant complex. (Lynn Pearson, p. 227) More recently, in 2013, another restoration of the building was completed. “Szerelmey* was selected to undertake the extensive cleaning, replacement and restoration works of the Michelin Building. Restoration works involved the replacement of a large number of...hand crafted faience tiles which were individually colour matched to blend with the existing pieces. In addition Szerelmey undertook a complete redecoration of the extensive metalwork on the exterior to return the building to its original splendour.” (http://szerelmey.wordpress.com/2013/11/12/michelin-building-restoration-works-complete/)

*[“Established since 1855,...Szerelmey...has become well known for the cleaning and repair of facades and the design, supply and installation of stonework for all types of external and internal applications.”] (http://www.szerelmey.com/)

|

| Bibendum in the café. |

The Early Years Of The Michelin Company

In 1829 Elizabeth Pugh Barker, the niece of a scientist who discovered that rubber was soluble in benzene, introduced rubber balls for children to France. In 1889 Édouard Michelin joined his brother, Andre, and took over the management of the J.G. Bideau company, the company originally founded by Elizabeth Barker’s husband, Edouard Daubrée, and renamed it Michelin & Co., which included a plant on 30 acres that employed fifty-two people. The Michelin plant then began to manufacture rubber brake pads. When, in 1891, a cyclist came to the Michelin plant for help to repair a tire and it took overnight to complete the repair, Édouard Michelin was determined to create a tire that was easy to repair. That same year Michelin filed for patents for detachable tires, and these were used by Charles Terront, the winner of the 1891 Paris-Brest-Paris bicycle race. In 1892 Michelin organized a race between Paris and Clermont-Ferrand and scattered nails over the road to prove that repairing a Michelin tire was not a big problem anymore. By 1895 the Michelin brothers drove an automobile, the Éclair, in the Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race. The Éclair was the first car to have pneumatic tires. In 1899 the 100kph barrier was broken by an electrically powered car, the Jamais Contente, which used Michelin tires. In 1906 The Michelin Tyre Company was founded in London. (http://www.michelin.com/corporate/EN/group/history)

Bibendum, The Michelin Man

“In 1894, the two founding brothers, André and Edouard Michelin, were visiting the Universal Exhibition in Lyon when they noticed a pile of tires on one stand. The overall effect was sufficiently evocative for Edouard to think that, with arms and legs, ‘it would make a man’. Some time afterwards, André singled out a sketch among drawings by the artist O'Galop. They adapted it to make a figure made of tires... and the character was born. The first posters appeared in 1898. ...The Michelin Man is called ‘Bibendum’, a word taken from the slogan "Nunc est bibendum" (Now is the time to drink - in this case drink obstacles) appearing on one of the earliest posters depicting the figure. In other countries than France, he is known as ‘The Michelin Man’… .” (http://www.michelin.com/corporate/EN/group/michelin-man)

|

The color lithograph of the poster above.

(Advertisement for Michelin, printed by Cornille & Serre, Paris (colour litho), French School, (20th century) / Private Collection / The Bridgeman Art Library)

In 1898 it was the illustrator O'Galop who drew Bibendum for the first time: the poster is a character made of tires, raising a glass full of nails and broken bottles, proclaiming "Nunc est

Bibendum, the Michelin tire drinks the obstacle!"

(http://www.audipassion.com/news/878/51/L-aventure-Michelin---un-musee-vivant-et-riche-en-informations/) |

The Tile Panels

|

| The Sloane Road side of the building. |

Michelin’s economic success was always intertwined with the bicycle and automotive industries, and later the developing aviation industry. “In the last decade of the 19th century, the Michelin brothers spurred the development of the bicycle and the automobile with a host of innovative products. These included the first removable bicycle tire, the first automobile tire and the first tire capable of handling speeds of over 100 km/h. They also conducted the first tests comparing pneumatic and solid tires, thus demonstrating a concern for fuel efficiency, even at that early date. In the first half of the 20th century, the brothers continued to improve the tire… .” (l’adventure MICHELIN; http://www.laventuremichelin.com/MFP_DP_Aventure_OK.pdf)

The early bicycle and auto races became venues for “proving” the value of the products of different companies. “In 1910, Michelin placed an order with Gilardoni Fils et Cie for ceramic panels to decorate its offices in Paris and London. Intended to celebrate Michelin’s motor sport successes since 1895, the panels showcased the cars in boldly colored, meticulously detailed renderings. (http://www.laventuremichelin.com/MFP_DP_Aventure_OK.pdf) The panels in London were actually a duplicate run of the originals in Paris. Many of the images were taken from drawings by the poster artist Ernest Montaut*. (Lynn Pearson, p. 227)

|

| The royal warrant mural. |

“One panel, made of smaller, more detailed tiles with a richer glaze, celebrates the royal warrant granted to the firm in 1908; it was made, probably in England, near the end of 1910.” (Lynn Pearson, p. 227)

*[“Ernest Montaut (1879–1909) was a French poster artist [...who] is credited with the invention of various artistic techniques, such as speed lines and distorting perspective by foreshortening to create the impression of speed. ...Montaut's printmaking career started in the late 19th century. He used a lithographic stone to produce an outline of the image, the Pochoir process… . Printed on the image was also a descriptive title advertising cars, tires, carburetors etc., and various sponsoring firms. The outlines were then painted by hand using watercolour paints [applied through stencils]. The process took a few days for each print and was quite labour-intensive. ...Montaut’s images display action, drama and derring-do [on] tortuous mountain passes covered at breakneck speed by the newly invented automobile. They document early developments in the history of motorised transport, such as motorboat racing, motorcycle and motor car racing, zeppelins and biplanes.”] (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernest_Montaut)

“In 1891, Le Petit Journal created the Paris–Brest–Paris road cycling race. Its editor Pierre Giffard promoted it as Paris-Brest et retour in his editorials which he signed ‘Jean-sans-Terre’. It is now established as the oldest long-distance cycling road event. Le Petit Journal described it as an ‘épreuve,’ a test of the bicycle's reliability and the rider's endurance. Riders were fully self-sufficient, carrying their own food and clothing and riding the same bicycle for the duration.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Petit_Journal) “The first (1891) Paris-Brest saw Michelin's Charles Terront and Dunlop's Jiel-Laval contest the lead. Terront prevailed, passing Jiel-Laval as he slept during the third night, to finish in 71 hours 22 minutes. Both had flats that took an hour to repair but [both] enjoyed an advantage over riders on solid tires.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris–Brest–Paris) “Cars entered in 1891 when a Peugeot successfully followed the field in the Paris-Brest cycle race.” (Maxwell G. Lay, Ways of the World: A History of the World’s Roads and the Vehicles That Used Them, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, 1992, p. 161)

|

Charles Terront pictured on the front page of the 20 September 1891

edition of Le Petit Journal after his Paris-Brest et retour victory;

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Petit_Journal

|

In 1894, “The first competition for automobiles with internal combustion engines can...be seen as a farewell to the older steam technology. A De-Dion-Bouton steam car was actually the first vehicle in the field across the finish line in 1894, but the vehicle was incredibly heavy and did not comply with the weight restrictions for the competition, and its achievement was rewarded with only second place.”

“In 1895, Emile Levassor [drove] a Panhard et Levassor car with a two-cylinder, 750-rpm, four-horsepower Daimler Phoenix engine over the finish line in the world's first real automobile race. Levassor completed the 732-mile course, from Paris to Bordeaux and back, in just under 49 hours, at a then-impressive speed of about 15 miles per hour. [...A] committee of journalists and automotive pioneers, including Levassor and Armand Peugeot, France's leading manufacturer of bicycles, spearheaded the Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race in order to capitalize on public enthusiasm for the automobile. ...The Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race highlighted France's superiority in automotive technology at the time, and established Panhard et Levassor as a major force in the fledgling industry. Its success spurred the creation of the Automobile Club de France in order to foster the development of the motor vehicle and regulate future motor sports events." (http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-auto-race-held-from-paris-bordeaux-paris)

|

The Michelin brothers in L’Éclair, “the Flash”.

|

In this 1895 race the Michelin brothers drove L’Éclair, “the Flash”, seen in the mural above, which used pneumatic--air-filled--tires. Made from a Peugeot chassis and a Daimler motor boat engine, Michelin mechanics gave birth to the "Flash", which derived its nickname from its propensity to run in a zig-zag fashion! After many adventures Edouard and André Michelin were among the few competitors to finish the race. They proved that "riding on air" was possible. Sure of their success, André Michelin had printed flyers in advance allowing them to conduct an advertising campaign after the arrival of L’Éclair in Paris! (http://www.audipassion.com/news/878/51/L-aventure-Michelin---un-musee-vivant-et-riche-en-informations/)

|

| Three races: the 1896 Marseille-Nice, the 1903 Paris-Madrid race, and the 1908 Circuit de Brescia. |

|

De Dion-Bouton was a French automobile manufacturer and railcar manufacturer operating from 1883 to 1932. The company was founded by the Marquis Jules-Albert de Dion, Georges Bouton, and Bouton's brother-in-law Charles Trépardoux. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_Dion-Bouton) Photo: The Bridgeman Art Library, #ASP74903)

|

“1896 appears to have been the pinnacle year in terms of development of the De Dion-Bouton Steam Bogie. ...The Steam Wagon and Steam Brake that were entered in the September, 1896 Paris-Marseilles-Paris race...were essentially converted Steam Bogies. ...The heavier Steam Brake driven by the Marquise de Chasseloup-Laubat was based on the De Dion-Bouton Steam Bogie Pattern No. 2… .” (http://serviside.blogspot.com/2012/01/beginning-of-end.html) “The No. 10 entry driven by the Marquise was described as: ‘Steam break for six, conducted by MM. the Marquise and the Count de Chasseloup Laubat, and carrying three mechanics.’ One of the mechanics was actually the fireman (stoker). The Marquise de Chasseloup-Laubat recounted that the No. 10 car...was beleaguered with ‘every break-down conceivable, except for an absolute explosion of the boiler.’ They spent a total of 47 hours making repairs, which put them far out of contention. [...Three] months later, after making improvements and modifications, the No. 10 was driven by the Count de Chasseloup Laubat to a decisive victory in the 145 mile Marseilles-to-Monte Carlo race (today known as the Marseilles-Nice-La Turbie race). It averaged a stunning 18.7 miles per hour. It would be this same Count Gaston de Chasseloup-Laubat who, on December 18, 1898, would set the world's first official Land Speed Record near Paris at 39.245 mph in a Jeantaud electric vehicle, earning him the sobriquet ‘The Electric Count.’” (http://serviside.blogspot.com/2011/12/de-dion-bouton-steam-bogie-part-2_4395.html)

|

| The 1899 Tour de France. |

The first Tour de France in 1899 “...was won by René de Knyff driving a Panhard et Levassor. [It was organized] by Le Matin, under the control of the Automobile Club de France… .” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tour_de_France_Automobile) The Panhard rode on Michelin tires.

|

| Fernand Charron in his Panhard, Paris-Amsterdam race, 1898. |

Fernand Charron drove a Panhard with Michelin tires in the Paris-Amsterdam race in 1898, as well as in the Paris-

Bordeaux race in 1900. “Fernand Charron (1886-1928) was a French pioneer of motor racing. Charron started his sporting career as a successful cyclist. Between 1897 and 1903 he took part in 18 car races, 4 of which he won: 1898 Paris-Amsterdam-Paris Race, 1898 Marseille–Nice, 1899 Paris-Bordeaux...and the inaugural 1900 Gordon Bennett Cup (Paris–Lyon). He drove mainly Panhard-Levassor cars.” (http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Fernand_Charron) Charron won the first Gordon Bennett Cup race (Paris-Lyon) in 1900: “The first international series was established by James Gordon Bennett, Jr., owner of the New York Herald. He proposed an annual event put on by automobile clubs of various European countries. ...The first Cup took place on May 29, 1900 between Paris and Lyon. Fernand Charron won in...nine hours and 23 minutes.” (Art Evans, “The Very First Automobile Races”, Victory Lane, July 2013, pp. 44-45; http://www.victorylane.com/articles/2013_07%20First%20Auto%20Race.pdf)

|

| Fernand Charron in his Panhard, Paris-Bordeaux race, 1900. |

|

| Mural depicting the Paris-Toulouse race of 1900, won by “Levegh”, and the Gordon Bennett Cup race of 1901, won by Giradot. |

“Motor racing was an unofficial sport at the 1900 Summer Olympics. Fourteen events were contested in conjunction with [the] 1900 World's Fair. Entries were by manufac-turers rather than drivers and competitors' names were not adequately reported at the time. The exceptions are the two classes of the Paris-Toulouse-Paris race, one class of which was won by Louis Renault [the small car class].” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motor_racing_at_the_1900_Summer_Olympics) The large car class was won by "Levegh" (Alfred Velghe), who drove a Mors automobile.

“The 1901 Gordon Bennett Cup, formally titled the II Coupe Internationale, was a motor race held on 29 May 1901, on public roads in France between Paris and Bordeaux, concurrently with an open-entry race over the same course. Initially, [French entries] were to defend the Cup against Great Britain, however prior to the start, the sole British entry was forced to fit tyres of foreign manufacture making it ineligible for the Cup. The race was therefore competed by three French entries, the maximum permitted from one country under the rules, guaranteeing that they would retain the Cup. Léonce Girardot driving a Panhard won the race and was the only competitor to finish, Fernand Charron driving a Panhard and Levegh driving a Mors retiring.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1901_Gordon_Bennett_Cup)

|

| Mural depicting the Paris-Berlin race of 1901 and the Paris-Vienna race of 1902. |

“[International road] racing appears to have been born in France where the first important contests were run from Paris to other cities and were called Les Grandes Epreuves (The Big Events). The first one was from Paris to Berlin and was a tough 687-mile dash. This race held during 1901 was won by Henri Fournier in his 60-h.p. Mors, a French car in which he was also victorious...in the previous Paris-Bordeaux Race. This second event, the Paris to Vienna race held during 1902, was perhaps one the toughest of all early races and has become a legendary event because of [the] stage over the mountain pass. [During the 1902 race] Baron Pierre de Caters ended up breaking a wheel in a shunt with Louis Renault, whose brother Marcel went on to win the event. De Cater’s and his Mors did manage to come in some four hours later after dealing with the wheel.” (http://theoldmotor.com/?p=46506)

|

Two of the autos that used Michelin tires in the 1902 Paris-Vienna race were the Panhard

that came in second, driven by Henri Farman and the Darracq, driven by

Karl Guillaume to victory in the voiturette category.

|

|

| It was reported that Messers. Bucquet and Labitte, who rode two Werner motorcycles in the Paris-Vienna race, had the best combined time of all the combined entries in the race. (“Continental Notes”, The Motor-Car Journal, Vol. IV, No. 191, Nov. 1, 1902, p. 681) |

|

| A streamlined racing auto in the Nice 1903 Rothschild Cup race |

The Rothschild Cup auto race in Nice in 1903 was won by Leon Serpollet. “After building the first flash boiler (1881) and a steam tricycle (1887), [Serpollet] designed a new steam engine (1891) using paraffin oil as fuel, which allowed a reduction in weight [of the auto]. For three consecutive years, his cars won the Rothschild Cup in Nice, reaching a [top] speed of 120 km / h.” (http://www.larousse.fr/encyclopedie/personnage/Serpollet/144006)

|

| Gabriel driving a Mors car in the Paris to Madrid race of 1903, known as "The Race of Death". |

The Paris–Madrid race of May 1903 was an early experiment in international auto racing. The cars drove through town streets at high speeds, and a number of accidents and a few fatalities occurred. “The race proved to be very difficult for the drivers: the dangers from the crowd added to the thick dust cloud raised by the cars. The weather had been dry for the prior two weeks, and dust covered the roads. Officials watered down just the first kilometer of road, and the short delay between the starting cars worsened the problem. Visibility dropped to a few meters, and people stood in the middle of the road to see the cars, becoming a persistent danger for the drivers. …[Fernand] Gabriel, who left [the start] as 168th...arrived third [at the finish, and...] was later recognized as the winner when the time slips were tallied up. ...Overall, half the cars had crashed or retired, and at least twelve people were presumed dead, and over 100 wounded. The actual count was lower, with eight people dead, three spectators and five racers[, including Marcel Renault].

The French Parliament reacted strongly to the news of the numerous accidents. An emergency Council of Ministers was called and the officers were forced to shut down the race in Bordeaux, transfer the cars to Spanish territory and restart from the border to Madrid. The Spanish government denied permission for this, and the race was declared officially over in Bordeaux. [One result was that there] would not be [an auto] race on public streets until the 1927 Mille Miglia.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris–Madrid_race)

|

| The café in the Michelin building leading into the shops and offices. |

|

| A tile panel depicting two races: Circuit des Ardennes, 1904; Coupe Gordon-Bennett, 1904; and the first Hackney-carriage to use Michelin tyres, in Paris in 1896. |

One report of the results of the 1904 Gordon Bennett Cup race states: “The contest seems from the start to have resolved itself into a struggle between Thery, of France, and Jenatyz, of Germany. ...The victory of the Frenchman was certainly one of the finest achievements ever seen in motor racing. To win both the elementary trial and then the Gordon-Bennett race Itself is no mean performance, and it showed both the coolness of the driver and the exceptional excellence of the motor when two such important races were won on the same car and by the same driver. It is very seldom indeed that the favorlte in such a race succeeds in getting home.” (“The Gordon-Bennett Race. Details of the Contest”, The Sydney (NSW) Morning Herald, July 29, 1904, p. 11; http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/14662009)

|

| The 1904 Circuit Des Ardennes auto race. George Heath driving his Panhard. |

“Born on Long Island, New York in 1862 George Heath became an American living in Paris during the 1890’s. Drawn by the lure of France’s blossoming automobile industry he soon secured a job at the Panhard & Levassor factory. He first appeared as a driver of one of the company’s race cars in 1898, finishing 13th in the grueling, 889-mile Paris to Amsterdam to Pau Race. The following year, in 1899, Heath demonstrated promise with a fourth place finish in the Paris to St. Malo Race, and a sixth at an auto race called the Tour de France. Aside from another sixth-place finish at Belgium’s Circuit Des Ardennes in 1902, Heath enjoyed little success until the greatest year of his driving career in 1904. That year he scored two major victories, the first at Circuit Des Ardennes and what proved to be the crowning achievement of his career, a win at the inaugural Vanderbilt Cup Race in his native Long Island, New York.” (http://www.vanderbiltcupraces.com/drivers/bio/heath)

|

| Arthur Duray driving a Lorraine Dietrich in the 1906 Circuit des Ardennes. |

Arthur Duray, an American born of Belgian parents, was an early aviator and auto race driver. Among other wins, he was first in the 1906 Circuit des Ardennes driving a Lorraine Dietrich. The Circuit des Ardennes “first started in 1902 when Charles Jarrot proved successful. In the latest contest the course measured...373 miles. There were 10 competitors…[and Duray won]...on a De Dietrich [which] registered an average of 66 miles an hour.” (“Circuit Des Ardennes”, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 Sept. 1906, p. 20)

The French Grand Prix began when, in a “...controversial move, the French pulled back from the previously recognized greatest road race in the world, the James Gordon Bennett Cup. They resented the rules of the Bennett Cup that only allowed three representatives from each car producing nation to participate. At the time, France was the preeminent automobile producing company in the world, with makes such as Panhard, Darracq, Mors, De Dietrich, Renault, Hotchkiss, Peugeot and several others. All were quality manufacturers, while other countries such as Germany (Mercedes) and Italy (Fiat) were represented by a single brand each. France's automotive industry did not feel the restrictive Bennett Cup rules afforded them the opportunity they deserved to showcase their products and announced the French Grand Prix for 1906." (http://www.firstsuperspeedway.com/articles/french-grand-prix-1906-szisz)

|

| Ferenc Szisz driving a Renault in the 1906 Grand Prix. |

|

“The French Grand Prix was a 64-mile course in the neighborhood of Le Mans and roughly in the form of a triangle. ...The first Grand Prix was a two-day affair… . Each day’s run was six laps (384 miles.) ...By the third lap [on the first day] the primary factor in the race’s outcome--tires--was apparent. Ferenc Szisz, driving a Renault, emerged the leader and would never be headed. Szisz, a Hungarian-born locksmith turned automotive engineer, stepped into the driving job after the death of company founder and racer Marcel Renault in the tragic Paris-Madrid 1903 race. Only the three Renaults and three Fiats were fitted with a new, patented wheel mount technology from Michelin that proved a huge advantage. Prior to this race, metal rims were permanently affixed to wooden wheels, making tire removal a laborious process. Race crews typically cut the rubber away with knives and then wedged new tires on. The advancement came in affixing separate rims with a system of steel wedges held in place by bolts. The bolts were loosened and the wedges, which were sandwiched with the rim in a groove in the wooden wheel, were tapped out with a hammer, and the tires were swapped out. Two trained men could change two tires in four minutes while previously the task required 16 minutes. The stark contrast was apparent when, on the sixth lap, Szisz arrived at a repair station to change tires. Panhard drivers Georges Teste and Henri Tart had already been at work changing theirs for 15 minutes before the Renault driver appeared. Szisz and his mechanic completed their work and were on their way while Teste and Tart were still toiling away.” (Mark Dill, “1906 Birth of the Grand Prix”; http://www.firstsuperspeedway.com/sites/default/files/French_Grand_Prix_1906_Szisz.pdf)

|

Renault driver J. Edmond. This Renault shows the new wheel and tire developed by Michelin and used in the 1906 French Grand Prix.

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:1906_French_Grand_Prix_Edmond.jpg)

|

|

| [Out of a starting field of 38 cars] Felice Nazzaro's Fiat led from [...lap nine] until the finish, completing the race over six and a half minutes ahead of second placed Ferenc Szisz. Nazzarro's average speed was 70.6 mph (113.6 km/h) for the race.(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1907_French_Grand_Prix) |

|

| Victor Hémery won the 1908, 438.25 mile, St. Petersburg-Moscow auto race. |

“Victor Hémery [...was born] on November 18, 1876, in Brest, France. [He was a trained] mechanic. From 1895 to 1900 he worked as a technician for Léon Bollée[; from] 1900 to 1906, [he headed…] the testing department and [became an] experienced racing driver with Darracq. In 1907 he was engaged as a racecar driver by Benz & Cie. Completely impoverished, Hémery at the age of 74 committed suicide on September 8, 1950, in Le Mans, France.” (“July 7, 1908: Mercedes wins the French Grand Prix”; 1557199_GP_Dieppe1908_D_e.rtf)

“Itala was a car manufacturer based in Turin, Italy from 1904-1934, started by Matteo Ceirano and five partners in 1903. ...The company experimented with a range of novel engines such as variable stroke, sleeve valve, and ‘A valve’ rotary types and at the beginning of World War I, offered a wide range of cars.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Itala) “Itala racing cars won the Coppa Florio in 1905, the Targa Florio in 1906 and the Peking-to-Paris race in 1907. 1908 was the first year for a fixed 'formula' for the Grands Prix of Europe. Itala built three four-cylinder cars for the 1908 season, utilizing drivers Alessandro Cagno, Henri Fournier and Giovanni Piacenza.” (http://classiccarweekly.wordpress.com/2012/06/21/itala-grand-prix-car/)

|

| Albert Guyot in his Delage racer with a de Dion engine. Grand Prix des Voiturettes, Dieppe, 1908. |

“Born in 1874, the flamboyant and extrovert Louis Delage had a lot of money and knew how to spend it. When he formed a company at Courbevoie-sur-Seine to design and build cars in 1905 he [...wanted] to keep the quality high. Almost immediately he entered his cars in racing in the voiturette class, one of them finishing second in the 1906 Coupe de l'Auto. Delage continued to be one of the leading manufacturers in pre-WW1 voiturette racing.

"Albert Guyot won the 1908 GP des Voiturettes at Dieppe with a de Dion engined Delage.”58 Albert Guyot (1881-1947) was an early automobile dealer who raced cars in

Europe and in the United States. Besides winning the 1908 Grand Prix des Voiturettes, he came in fourth and third in the [1913] and [1914] Indy 500 races.59 “He was one of four drivers who entered...the 1921 French Grand Prix [driving a Duesenberg], the first [Grand Prix] in which a US make participated. Jimmy Murphy won

with his Duesenberg 183; Guyot finished 6th.

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Guyot) Guyot tested cars from 1906 to World War I, and after 1925 he built cars. (http://www.oldracingcars.com/driver/Albert_Guyot)

|

| Christian Lautenschlager in his Mercedes in the 1908 French Grand Prix. |

In the 1908 French Grand Prix, Mercedes took first and third places and Benz came in second. The "...two German companies had the winners' rostrum all to themselves... . ...The conditions were not ideal on the 7th of July 1908 in the French coastal town of Dieppe. Though the weather was friendly, on the day before the vehicles of the voiturette class – small, lightweight automobiles – had put the course into a wretched state during their race. Overnight repair work did little to change the situation. The track was dotted with potholes, and deep ruts had been carved especially in the curves. Things would not be improving during the course of the event, so it was clear from the beginning that pneumatics, a widely used term for tires in those years, would be a decisive factor in the competition.

“A total of 769.88 kilometers in ten laps had to be covered on public roads closed to other traffic. Lined up at the start of the competition, organized by the Automobile Club de France (ACF), were racecars of the Grand Prix category – famous drivers in famous cars. For instance, Camille Jenatzy in a Mors, Vincenzo Lancia in a Fiat, Fritz Opel in an Opel, Dario Resta in an Austin, Fritz Erle, René Hanriot and Victor Hémery in Benz 120 hp cars, and, of course, the DMG [Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft] team, consisting of Christian Lautenschlager, Willy Pöge and Otto Salzer, who took the start in 140 hp Mercedes.

“...Despite the unfavorable conditions, especially for Daimler things worked out almost perfectly in Dieppe: Lautenschlager crossed the finish line in first place after six hours, 55 minutes and 43 seconds, barely nine minutes ahead of the runner-up – and with the last set of tires on board. His average speed over the entire distance was impressive 111.1 km/h. ...Christian Lautenschlager [...was born] on April 13, 1877, in Magstadt, not far from Stuttgart. He became a mechanic and, after completing his apprenticeship, worked at various factories in Germany and other countries. In 1899 he came to Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft as a mechanic. In 1905 he went to the racing department as foreman. His two victories in the 1908 and 1914 Grand Prix make Lautenschlager one of the all-time greats of international motor racing. He passed away on January 3, 1954, in Fellbach near Stuttgart.” (“July 7, 1908: Mercedes wins the French Grand Prix”; 1557199_GP_Dieppe1908_D_e.rtf)

|

This mural was hidden behind some boxes in the cafe. It portrays Jules Goux in his Lion-Peugeot in 1909

|

Giuppone won the 1909 Coupe de l'Auto with Goux second. (http://www.grandprix.com/ft/ftjs006.html) In the III Corsa Vetturette Madonie in 1909, Jules Goux was first.(http://www.teamdan.com/archive/gen/1909/1909.html)

|

| Jules Goux. (http://www.ucapusa.com/race_drivers.htm) |

"Jules Goux, [1885-1965], was a Grand Prix motor racing champion and the first Frenchman, and the first European, to win the Indianapolis 500. ...Jules Goux began racing cars in his early twenties. Success came in 1908 on a circuit set up on roads around Sitges, near Barcelona, Spain, when he won the Catalan Cup, a victory he repeated the following year. Because of his racing success, along with Georges Boillot, he was invited by Peugeot Automobile to race for their factory team. As part of a four-man design team led by Paul Zuccarelli and Ernest Henry, Goux helped develop a racecar powered by a radically new Straight-4 engine using a twin overhead cam. Jules Goux won the 1912 Sarthe Cup at Le Mans driving a Peugeot, and in 1913 he traveled with the team to the United States to compete in the Indianapolis 500 race. Goux won the race, becoming the first French person to ever do so." (http://pages.rediff.com/jules-goux/717733)

|

| The Coupe des Voiturettes was held in Boulogne, France in 1910. |

|

© Agence Rol. Agence photographique.

|

|

”Latham's Machine fitted with Michelin aeroplane sheeting”: ceramic tiles manufactured by

|

Early in the 20th century the Michelin Company became interested in aircraft and in the production of products for the new aviation industry. “In addition to promoting overland travel, the Michelin brothers also had great admiration for aviation’s pioneers, encouraging them with prizes and challenges that few people believed were attainable at the time. In 1908, they offered 100,000 francs to the first person who could fly a plane from Paris to Clermont-Ferrand[, the site of the Michelin factory,] and land on the peak of the nearby Puy-de-Dôme. Some said it would take ten years for such a feat to happen, while the less optimistic believed there was no chance at all. And yet the challenge was successfully met in 1911.” (l’adventure MICHELIN; http://www.laventuremichelin.com/MFP_DP_Aventure_OK.pdf)

According to one source, “Unprecedented feats in aviation are being performed in France by Mr. Hubert Latham, the young aeroplanist… . He has beaten every record except that of the Wright Brothers as regards time in the air and distance travelled, while in regard to manoeuvring he has beaten even the Wright Brothers… . Mr. Latham is only 25 years of age, and though an experienced balloonist has only within the last few months experimented with heavier than air machines. His monoplane, the Antoinette IV, was built to his. designs by M. [Leon Levasseur]… .” (MARVELS OF THE MONOPLANE. MR. LATHAM'S WONDERFUL FEATS. TRAVELS LIKE A BIRD”, The Kalgoorlie Miner (Australia), 26 July 1909, p. 5)

“Hubert Latham [1883-1912] was almost the first person to fly an airplane over the British Channel. If the French aviator and adventurer was discouraged when his first attempt came up short, he never showed it. As he bobbed in the waves waiting to be retrieved by a passing vessel, Latham casually smoked a cigarette in the cockpit of his wrecked Antoinette.* Adventure was his business, and keeping a cool head was a prerequisite in the daredevil profession. Although he failed to be the first to reach the White Cliffs of Dover his flight proved to be historic in another way. He had completed the world’s first landing of an aircraft in the sea. ...Air shows and aerial competitions were becoming more and more popular across Europe and America. Lots of prize money, advertising opportunity for [the] Antoinette engine, and risk remained to satisfy the adventurer’s hunger. ...Latham throttled his plane high into the air and set altitude records in Reims, France, and in Mourmelon-le-Grand. According to legend, he became the first to fly an airplane backwards, when against better judgement, he flew into a gale during a competition in Blackpool, England in 1909. ...In 1910 ...the A.S. Abell Company, owners of The Baltimore Sun, offered a $5,000 prize for any aviator who would...dazzle the crowds by flying high above [Baltimore]. [...On] November 7, 1910...Latham and his fifty-horsepower Antoinette took off from Halethorpe and began his plotted path over the city. ...Twenty-five miles and forty-two minutes later Hubert Latham landed safely back at Halethorpe.” (“Antoinette in the Air: Hubert Latham and His Historic Flight Over Baltimore, 1910” in underbelly, March 7, 2013; http://www.mdhs.org/underbelly/2013/03/07/antoinette-in-the-air-hubert-latham-and-his-historic-flight-over-baltimore-1910/)

|

| Latham in his Antoinette monoplane beginning his flight over Baltimore in November 1910. (BCLM, MdHS, MC1985-2; see underbelly article above) |

*[“The Antoinette engine was originally developed [in 1907 by Léon Levasseur who supplied Latham with engines during his stint as a speedboat racer. Later, after Latham was inspired by performances by Wilbur Wright (who was trying to sell an engine of his own) he sought out a company that would train him as a pilot to promote their product. In the meantime, Levasseur had formally established the Antoinette Company (based on the precursor engine from the speedboats) and happily obliged Latham’s request. [Latham] quickly mastered the engine and became the company’s top pilot.”] (underbelly, op. cit.)

During World War I the Michelin Company built aircraft for France.

Gilardoni Fil et Cie

The pottery that made the Michelin tile panels was Gilardoni Fil et Cie, which began as a roofing tile company in Alsace in the 1830s. The brothers, François Xavier (1807-1893) and Thiebaut Joseph (1805-1864) Gilardoni, built a factory at Altkirch in 1835 to manufacture ceramic roofing products. The Gilardoni brothers invented and patented the first interlocking roof tile in 1841, which caused a “...great change in tile making[...because, now,] tiles could be economically moulded into more complex shapes,...the joints could be made reasonably weathertight without a large overlap, and the thickness was reduced without loss of strength. This meant that a given number of tiles covered a greater area, which reduced the cost of the tiling itself, and the weight was considerably less, which made a lighter and cheaper substructure possible. These [...were] known as Gilardoni tiles [after the inventors].

|

| Interlocking Gilardoni Roofing Tiles. (R.V.J. Varman, “The Marseilles or French Pattern Tile in Australia”, The Australian Society for Historical Archaeology, Occasional Paper No. 3, University of Sydney, NSW, 2006, p. 25) These tiles were called “rhombic tiles” because of a raised diamond in the middle of the tile that prevents it from collapse upon drying and which gives it greater rigidity. (http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gilardoni_Frères) |

“...The Gilardonis patented a similar tile in England in...1855. Their tiles were shown at the Paris Exposition in 1855, and a report upon this in the Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal of 1857 is the earliest available description of them.” (6.06 Bricks and Tiles: Roofing Tiles: 07, p. 6.06.3; http://mileslewis.net/australian-building/pdf/06-bricks-tiles/6.06-roofing-tiles.pdf) “[...The interlocking roof] tile cannot be made by hand such as the Roman or Flemish tile, the [interlocking] tile needs metal or plaster dies and at least hand press machinery for production.” (R.V.J. Varman, “The Marseilles or French Pattern Tile in Australia”, The Australian Society for Historical Archaeology, Occasional Paper No. 3, University of Sydney, NSW, 2006, p. 1)

The invention of the Gilardoni brothers not only transformed roof coverings, but also the whole terra cotta industry because the Gilardoni brothers had to develop new methods and machines to create their products. The new tiles demanded a precision which came about by using steam powered machines that allowed the mass production of parts. (http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gilardoni_Frères) The Gilardoni factory was located in Pargny-sur-Saulx and produced roof tiles and bricks[,...as well as] decorative ceramics, decorated friezes, pediments, lanterns, and medallions. (http://www.lunion.presse.fr/article/a-la-une/la-saga-des-tuileries-de-pargny-sur-saulx)

The original plant in Altkirch was not sufficient for their needs and a second factory was built in the same department, in Dannemarie, in 1864. After the war of 1870 with Germany, this department was annexed by Germany. Then a group of associates of Gilardoni Fil founded a third factory in Bois-du-Roi in 1873. (http://ceramique-architecturale.fr/?p=633) In 1880, the son of François-Xavier (Xavier-Antoine Gilardoni) merged Gilardoni Fil et Cie with Alfred Brault. The Gilardoni factory was then based in Choisy-le-Roi[, a suburb of Paris]. Gilardoni won a gold medal in 1900 for ceramic ornamentation at the Universal Exhibition in Paris. In 1902 Xavier Pierre Gilardoni was granted US Patent # US706926 A for a steam operated tile press which was assigned to Gilardoni Fils, A. Brault et Cie. The Paris headquarters for this company was 38 Rue de Paradis. In 1986 Gilardoni Fil et Cie was merged with Tuileries Huguenot Fenal and then in 1999 it became part of Imérys Toiture, the leading French clay roof tile company. (http://fr.academic.ru/dic.nsf/frwiki/237570; http://www.pargnysursaulx.fr/Histoire/Tuileries/ [In 2004, the Museum of roof tile was opened in the Chapel of St. Therese, Pargny-sur-Saulx. Besides other historic roof tiles, much of the exhibition is dedicated to the mechanical tile developed by the Gilardoni brothers who patented their system in 1841, and the accessories of the industry: bank tiles, tiles chaperone, pediments, ears, roof vents, ridge, etc.]; http://www.clayandslateroofingproducts.co.uk/imerys-clay-roof-tiles/)

In 1896, Xavier Gilardoni, owner of the tile company in Choisy-le-Roi, commissioned the architect Leon Bonnenfant to build his private house. It combines multicolored bricks and elements of architectural ceramics. This building is one of the last truly significant works of the Gilardoni tile and earthenware industry in Choisy-le-Roi that still exists. (Gilardoni residence; and http://www.culture.gouv.fr/public/mistral/merimee_fr?ACTION=CHERCHER&FIELD_8=REF&VALUE_8=IA00082300)

The Gilardoni Fil et Cie factory no longer exists on the Rue Sébastopol in Choisy-le-Roi. All that is left in Rue Sébastopol is this piece of wall with a ceramic design.

This company made a variety of different ceramic products, and Gilardoni Fil won awards in many international exhibitions--Paris in 1855 and in the Universal Exhibitions of 1867, 1889, and 1900 in Paris, as well as the Grand Prize in London in 1908. (http://www.patrimoineindustriel-apic.com/parcours/pargny%20sur%20saulx/livret%20debrand/historique%20gilardoni.htm)

|

| The cover of the 1898 Gilardoni catalog and one of the catalog pages of products. |

|

Vase for the Castel Béranger c.1897, glazed stoneware 9.5 cm. in height.

Hector GUIMARD* (1867-1942), designer, Xavier RAPHANEL (1876-1957), modeler.

GILARDONI FILS, A. BRAULT ET CIE, manufacturer.

(Accession No: NGA 94.1088, National Gallary of Australia; http://artsearch.nga.gov.au/Detail-LRG.cfm?IRN=2079)

|

*[Hector Guimard was a designer and an avant garde architect. He designed the entrance pavilions for the Paris Metro in 1899, the ceramic facade of the Hôtel Jassedé in 1893, and the stoneware decorations--such as the vase above--for an apartment block, Castel Béranger at 14 Rue La Fontaine in 1897-98, among others.] (Hans van Lemmen and Bart Verbrugge, Art Nouveau Tiles, Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York, NY, 1999, pp. 45-46)

*[“In the 1880s Vincent van Gogh lived at 54, rue Lepic with his brother, Theo, near the Moulin de la Galette, the rustic outdoor dancehall that he, Renoir, and Toulouse-Lautrec each captured on canvas. Even today,...the lower stretch of the rue Lepic remains the province of locals going about their business. Since shortly after the turn of the last century, Lux Bar, a simple café-bistro, has operated here among the bakery shops and horse butchers… . Inside [...is featured] a tile mural of the Moulin Rouge, the famed 1889 cabaret just around the corner on the boulevard de Clichy.”] (Ellen Williams, The Historic Restaurants of Paris, The Little Book Room, New York, NY, 2002, pp. 231-232)

Michelin in Paris

In the beginning of this article I mentioned that the tile panels in Michelin House, London were duplicates of Gilardoni Fil et Cie tile panels in the Michelin headquarters in Paris. I have Peter Olson, who writes an excellent blog about “secret” places in Paris, to thank for discovering what happened to the original set of tiles in Paris. In 1970 Michelin moved from its old headquarters at 97 Boulevard Pereire to a new building at 46 Avenue de Breteuil. The ceramic panels were removed and stored partly in Paris and partly in Clermont-Ferrand, where Michelin had a major factory complex, and were all but forgotten. In about 2000 the panels were rediscovered and restoration was begun.

In 2009 Michelin opened “L’aventure Michelin”, a new Michelin museum--2000 square meters on two levels--located on Michelin’s Cataroux site, north of the city of Clermont-Ferrand. Cataroux is the largest industrial establishment of the Michelin group in Clermont-Ferrand. (http://www.audipassion.com/news/878/51/L-aventure-Michelin---un-musee-vivant-et-riche-en-informations/)

*****

I wish to thank Peter Olson, the author of the blog, “Peter’s Paris as Seen by a Retired Swede” (http://www.peter-pho2.com/), for his help in locating articles and photos about Gilardoni Fil et Cie and Michelin, France for me, and for the use of his photo of the Lux Bar. Also, thanks to Lynn Pearson, author of Tile Gazetteer, the best introduction to architectural ceramics in the UK, and the guide I used when I visited London, and to Paul Thompson of West Yorkshire Images for the photo of the Thornton Building in Leeds.

*****

This is the title of a brief article by Jessica Smith published on docomomo united states (http://docomomo-us.org) about the New York City Housing Authority and the history of five public housing projects on Manhattan's Lower East Side. It begins: "This fall, as part of the Documentation and Interpretation course in Pratt Institute’s Historic Preservation program, five graduate students (including myself) were given a project that involved researching five of New York’s public housing developments on the Lower East Side. We were each assigned one site that included the Smith Houses, the LaGuardia Houses, the Baruch Houses, the Wald Houses, and Jacob Riis Houses. The project had two objectives: one was to provide research and consultation for the New York Environmental Law and Justice Project (NYELJP) who, in November, brought a lawsuit against the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) in an attempt to stop their recently proposed Land Lease plan. ...The second objective worked in tandem with the first, in that, it sought to provide us with experience in writing and submitting an application for a National Register of Historic Places designation." Read more on docomomo-us.org.

_finished_1st,_ruled_ineligible_for_prize.jpg)